In the late 1970s, M. Stanley Whittingham was the first to describe the concept of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, an achievement for which he would share the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Yet even he couldn’t have anticipated the complex materials science challenges that would arise as these batteries came to power the world’s portable electronics.

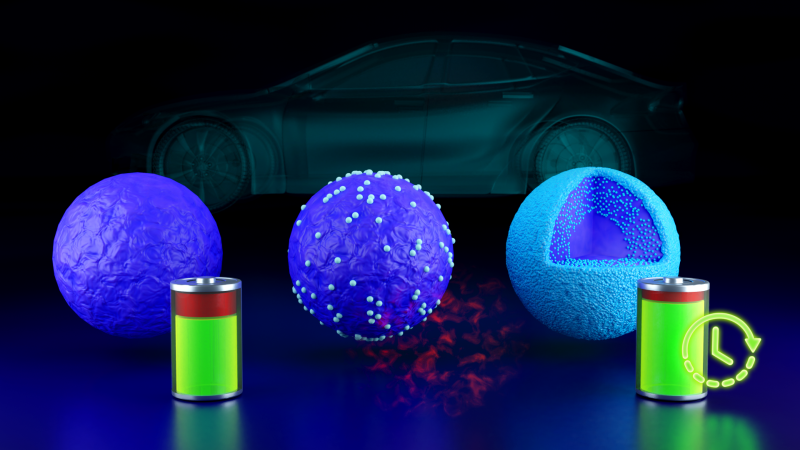

One persistent technical problem is that every time a new lithium-ion battery is installed in a device, up to about one-fifth of its energy capacity is lost before the device can be recharged the very first time. That’s true whether the battery is installed in a laptop, camera, wristwatch, or even in a new electric vehicle.

The cause is impurities that form on the nickel-rich cathodes—the positive (+) side of a battery through which its stored energy is discharged.

To find a way of retaining the lost capacity, Whittingham led a group of researchers that included his colleagues from the State University of New York at Binghamton (SUNY Binghamton) and scientists at the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Brookhaven (BNL) and Oak Ridge National Laboratories (ORNL). The team used x-rays and neutrons to test whether treating a leading cathode material—a layered nickel-manganese-cobalt material called NMC 811—with a lithium-free niobium oxide would lead to a longer lasting battery.

The results of the study, “What is the Role of Nb in Nickel-Rich Layered Oxide Cathodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries?” appear in ACS Energy Letters.

“We tested NMC 811 on a layered oxide cathode material after predicting the lithium-free niobium oxide would form a nanosized lithium niobium oxide coating on the surface that would conduct lithium ions and allow them to penetrate into the cathode material,” said Whittingham, now a SUNY distinguished professor and director of the Northeast Center for Chemical Energy Storage (NECCES), a DOE Energy Frontier Research Center led by SUNY Binghamton.

Lithium batteries have cathodes made of alternating layers of lithium and nickel-rich oxide materials (chemical compounds containing at least one oxygen atom), because nickel is relatively inexpensive and helps deliver higher energy density and greater storage capacity at a lower cost than other metals.

But the nickel in cathodes is relatively unstable and therefore reacts easily with other elements, leaving the cathode surface covered in undesirable impurities that reduce the battery’s storage capacity by 10-18% during its first charge-discharge cycle. Nickel can also cause instability in the interior of the cathode structure, which further reduces storage capacity over extended periods of charging and discharging.

To understand how the niobium affects nickel-rich cathode materials, the scientists performed neutron powder diffraction studies at the VULCAN engineering materials diffractometer at ORNL’s Spallation Neutron Source (SNS). They measured the neutron diffraction patterns of pure NMC 811 and niobium-modified samples.

“Neutrons easily penetrated the cathode material to reveal where the niobium and lithium atoms were located, which provided a better understanding of how the niobium modification process works,” said Hui Zhou, battery facility manager at NECCES. “The neutron scattering data suggests the niobium atoms stabilize the surface to reduce first-cycle loss, while at higher temperatures the niobium atoms displace some of the manganese atoms deeper inside the cathode material to improve long-term capacity retention.”

The results of the experiment showed a reduction in first-cycle capacity loss and an improved long-term capacity retention of greater than 93 percent over 250 charge-discharge cycles.

“The improvements seen in electrochemical performance and structural stability make niobium-modified NMC 811 a candidate as a cathode material for use in higher energy density applications, such as electric vehicles,” said Whittingham. “Combining a niobium coating with the substitution of niobium atoms for manganese atoms may be a better way to increase both initial capacity and long-term capacity retention. These modifications can be easily scaled-up using the present multi-step manufacturing processes for NMC materials.”

Whittingham added that the research supports the objectives of the Battery500 Consortium, a multi-institution program led by the DOE’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. The program is working to develop next-generation lithium-metal battery cells delivering up to 500-watt hours per kilogram versus the current average of about 220-watt hours per kilogram.

The research was supported by the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Vehicle Technologies Office, and used resources at BNL’s National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) and at ORNL’s Spallation Neutron Source.

SNS and NSLS-II are DOE Office of Science user facilities. UT-Battelle LLC manages ORNL for the DOE Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit www.energy.gov/science. –by Paul Boisvert